Makarioi: The Greek Roots of the Beatitudes

A scholarly edition of this page, including full Chicago-style citations and a complete bibliography, is available in the Downloads section.

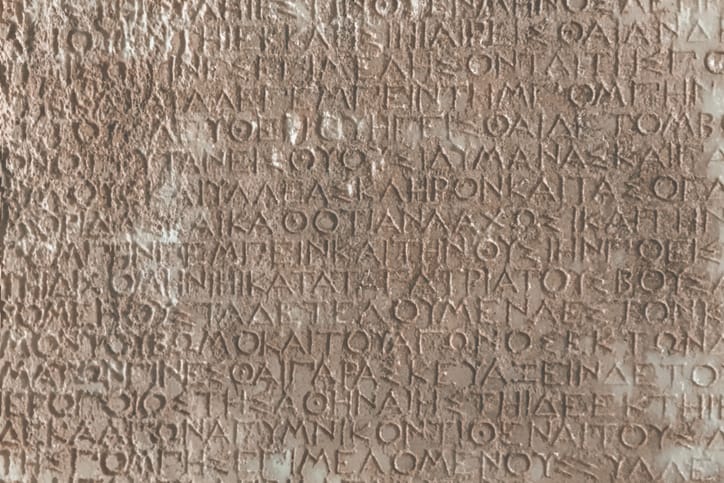

Translation is never neutral. Every word carries choices—and every choice carries meaning. In this chapter, we return to the original Greek of the Beatitudes in Matthew 5:3-12, not to nitpick grammar, but to uncover the deeper texture of Jesus' words and explore how translation decisions have shaped centuries of interpretation.

These blessings were not whispered in a vacuum. They were spoken in a charged cultural, religious, and linguistic context—shaped by both Hebrew wisdom and Greco-Roman rhetoric. The Greek language of Matthew preserves that context in ways our English versions often obscure, while also revealing the theological and pastoral choices that translators have made across the centuries.

Let's walk through each Beatitude, focusing on key Greek terms, their possible Hebrew or Aramaic substrates, and what they suggest—or resist—in translation.

The Foundation: Makarioi

Before examining individual Beatitudes, we must understand the foundational term that begins each blessing: makarioi(μακάριοι). Traditionally translated "blessed," this word doesn't imply a moral reward or divine transaction earned through behavior. It's closer to flourishing, fortunate, or deeply satisfied—describing a state of well-being rather than a religious status.

The term echoes the Hebrew ashrei (אַשְׁרֵי) from Psalm 1 and throughout the Psalter—not a legal designation, but a description of the genuinely happy life. This distinction has profound implications: the Beatitudes are not promises contingent on performance but recognitions of where true flourishing is already found, even when the world sees only poverty, mourning, or persecution.

The translation choice between "blessed," "happy," and "flourishing" reflects different theological emphases that have shaped Christian interpretation for centuries. "Blessed" suggests divine favor, "happy" implies emotional satisfaction, while "flourishing" points toward comprehensive well-being that encompasses but transcends both.

1. "Blessed are the poor in spirit..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi ptōchoi tō pneumati, hoti autōn estin hē basileia tōn ouranōn.

Ptōchoi (πτωχοί): Not just the "poor," but the absolutely destitute—those who have nothing and must beg for survival. The term comes from ptōssō, meaning "to crouch" or "cower," suggesting people who literally bow down to ask for help. In other Gospel contexts (especially Luke), this clearly refers to material poverty. But Matthew adds the crucial qualifier...

Tō pneumati (τῷ πνεύματι): "in spirit." This dative of respect has generated centuries of interpretive debate. Is Matthew spiritualizing poverty to make it more palatable to his audience? Or is he clarifying the kind of poverty—spiritual destitution and recognition of one's need for God—that opens the heart to divine grace? Most contemporary scholars favor the latter interpretation: this is about inner posture—recognizing one's emptiness and complete dependence on God.

The Hebrew/Aramaic background likely draws from the tradition of the anawim (עֲנָוִים)—the humble poor who combined material need with spiritual dependence on God. These were people who had learned that human resources are insufficient and that true security comes only from divine mercy.

2. "Blessed are those who mourn..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi penthountes, hoti autoi paraklēthēsontai.

Penthountes (πενθοῦντες): A strong word for grief, typically used for mourning the dead. This isn't general sadness or mild disappointment—it's deep, soul-shaking lament. The present participle suggests ongoing mourning, not just momentary sorrow. In the Septuagint, this term often translates Hebrew words for ritual mourning and prophetic lamentation over sin and injustice.

The mourning likely encompasses multiple dimensions: grief over personal sin, sorrow for others' suffering, and lament over the world's brokenness. The prophetic tradition of Israel provides the background—those who "sigh and groan over all the abominations" (Ezekiel 9:4) are marked for divine protection.

Paraklēthēsontai (παρακληθήσονται): "They will be comforted." The root parakaleō means not just emotional comfort, but to be called alongside—to receive the presence and support of another. The word shares its root with Paraklētos, the Comforter or Advocate, referring to the Holy Spirit in John's Gospel (14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7).

This blessing promises not just the cessation of grief, but the presence of God in the midst of loss—divine companionship that transforms suffering without necessarily removing it.

3. "Blessed are the meek..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi praeis, hoti autoi klēronomēsousin tēn gēn.

Praeis (πραεῖς): Often rendered "meek," but this translation is deeply misleading in contemporary English. The term connotes gentle strength or power under control. Aristotle used it in his Nicomachean Ethics to describe the virtue between the extremes of being overly angry and never being angry—someone who is angry at the right time, in the right way, for the right reasons, and never ruled by anger.

In biblical usage, it describes those who are powerful but restrained—like Moses, called "very meek (anav) above all people who were on the face of the earth" (Numbers 12:3). Moses was hardly a passive figure; he confronted Pharaoh, led a nation, and challenged rebellion. His "meekness" was strength disciplined by humility and trust in God.

Klēronomēsousin (κληρονομήσουσιν): "They will inherit"—a verb deeply tied to covenantal land promises in the Hebrew Bible. The allusion to Psalm 37:11 ("the meek shall inherit the land") would have been unmistakable to Matthew's Jewish audience. This is not about passivity receiving reward, but about the patient faithfulness that ultimately endures when aggressive power exhausts itself.

This is not weakness but the quiet power of those who do not grasp—and so receive what cannot be seized by force.

4. "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi peinōntes kai dipsōntes tēn dikaiosynēn, hoti autoi chortasthēsontai.

Peinōntes kai dipsōntes (πεινῶντες καὶ διψῶντες): Strong, visceral verbs for hunger and thirst—this is craving, yearning, not mild interest or casual desire. The present participles suggest ongoing, persistent longing. This echoes the Psalmic tradition of thirsting for God (Psalms 42:1-2; 63:1) and the prophetic call to "seek the Lord while he may be found" (Isaiah 55:6).

Dikaiosynē (δικαιοσύνη): Perhaps the most theologically freighted term in the Beatitudes. Traditionally translated "righteousness," but the Greek encompasses both personal virtue and social justice. In the Septuagint, it often translates Hebrew tzedakah (צְדָקָה), which includes legal justice, ethical behavior, and covenantal faithfulness. The term includes both being right with God and making things right in the world.

Different Christian traditions have emphasized different aspects of this rich term: Protestant traditions often stress personal righteousness before God, while Catholic and Orthodox traditions have maintained stronger emphasis on social justice dimensions. Liberation theologians have particularly emphasized the social justice implications, while evangelical traditions have focused on personal righteousness through faith.

Chortasthēsontai (χορτασθήσονται): "They will be filled"—literally, satisfied like animals after feeding. It's a surprisingly earthy verb for spiritual satisfaction, suggesting that God's response to spiritual hunger is not ethereal but abundantly material—a feast rather than a snack.

This Beatitude speaks of an aching soul and promises God's abundance in response to holy dissatisfaction with injustice and spiritual mediocrity.

5. "Blessed are the merciful..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi eleēmones, hoti autoi eleēthēsontai.

Eleēmones (ἐλεήμονες): "The merciful." Not merely those who feel compassion, but those who act on it. The term implies extending forgiveness, aid, and solidarity to others—especially the undeserving or vulnerable. In Jewish tradition, this echoes God's chesed (חֶסֶד)—steadfast, loyal love that maintains covenant relationship even when the other party fails.

Eleēthēsontai (ἐλεηθήσονται): "They will receive mercy." The verbal form mirrors the adjective, creating a rhythmic reciprocity of giving and receiving. This isn't mechanical cause-and-effect but recognition of spiritual coherence: mercy opens the heart to receive mercy, while unmerciful hearts close themselves to grace.

In this Beatitude, Jesus affirms a core biblical principle: the merciful heart becomes the vessel through which God's mercy flows both outward to others and inward to oneself.

6. "Blessed are the pure in heart..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi katharoi tē kardia, hoti autoi ton Theon opsontai.

Katharoi (καθαροί): "Pure"—from which we get "catharsis." The term can mean physically clean, ritually pure, or morally clear. In this context, it likely means undivided or single-minded. Classical usage often referred to ritual or moral purity, but here it suggests integrity and clarity of intention—a heart not pulled in competing directions by conflicting loyalties.

Tē kardia (τῇ καρδίᾳ): "In heart." In Hebrew and Greek thought, the heart (lev in Hebrew, kardia in Greek) is not primarily the seat of emotion but the center of thought, will, and moral choice. A pure heart is not naive or sentimental—it is undivided, wholly oriented toward God without the internal fragmentation that comes from mixed motives.

Ton Theon opsontai (τὸν Θεὸν ὄψονται): "They will see God." A striking promise that echoes the theophanies of Moses (Exodus 33:18-23) and the Psalmic tradition: "Who shall ascend the hill of the Lord? And who shall stand in his holy place? Those who have clean hands and a pure heart" (Psalm 24:3-4).

This promise of vision is not limited to eschatological fulfillment but includes present spiritual perception—the ability to recognize God's presence and activity in the world. The pure in heart see clearly because they are not looking through the fog of divided loyalties and hidden agendas.

7. "Blessed are the peacemakers..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi eirēnopoioi, hoti huioi Theou klēthēsontai.

Eirēnopoioi (εἰρηνοποιοί): "Peacemakers." This is a remarkably rare Greek word, found nowhere else in the New Testament and rarely in classical literature. It denotes not peaceful people or those who love peace, but those who actively make peace—who reconcile, heal divisions, and build wholeness where there was brokenness.

The Hebrew concept of shalom (שָׁלוֹם) lies behind this term—not merely the absence of conflict but the presence of right relationship, justice, and flourishing. Peacemaking in biblical terms often requires confronting injustice rather than simply maintaining calm.

Huioi Theou (υἱοὶ Θεοῦ): "Sons of God," or more inclusively, "children of God." In biblical idiom, to be called someone's child is to share their character. Thus, peacemakers resemble the God of peace—they participate in divine nature by doing divine work.

This Beatitude affirms reconciliation as fundamentally divine activity—and those who engage in it as God's own family members.

8. "Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake..."

Greek: Makarioi hoi dediōgmenoi heneken dikaiosynēs, hoti autōn estin hē basileia tōn ouranōn.

Dediōgmenoi (δεδιωγμένοι): A perfect passive participle—"those who have been and continue to be persecuted." The perfect tense suggests ongoing effects of past persecution, while the passive voice indicates that the persecution comes from external forces rather than self-inflicted suffering.

Heneken dikaiosynēs (ἕνεκεν δικαιοσύνης): "Because of righteousness"—again that rich word dikaiosynē, encompassing both personal integrity and social justice. The persecution comes not because these people are obnoxious or confrontational, but because their way of life challenges systems that benefit from injustice.

This Beatitude returns to the promise of the first: the poor in spirit and the persecuted both "possess the kingdom." This creates an inclusio—a literary bracket that frames the entire series, emphasizing that God's reign belongs to those whom the world excludes or oppresses.

9. "Blessed are you when people insult you..."

Greek: Makarioi este hotan oneidisōsin humas kai diōxōsin kai eipōsin pan ponēron kath' humōn pseudomenoi heneken emou.

This final blessing shifts dramatically from third person ("they") to second person ("you"), making the teaching suddenly personal and direct. The shift signals a movement from general principle to direct application—from describing the kingdom's citizens to addressing Jesus' actual followers.

Oneidisōsin (ὀνειδίσωσιν): "They insult or revile you"—public shame and verbal attack.

Diōxōsin (διώξωσιν): "They persecute you"—active pursuit and harassment.

Eipōsin pan ponēron (εἴπωσιν πᾶν πονηρὸν): "They say all kinds of evil against you"—slander and character assassination.

Pseudomenoi (ψευδόμενοι): "Falsely"—the accusations are lies, not legitimate criticism.

Heneken emou (ἕνεκεν ἐμοῦ): "Because of me"—the persecution comes specifically because of allegiance to Jesus, not because of the disciples' own failings or provocative behavior.

This personal address acknowledges that following Jesus brings specific opposition. The blessing extends not to all suffering, but to suffering that results from faithful discipleship.

Hebrew and Aramaic Background

While we have the Beatitudes in Greek, Jesus likely spoke them in Aramaic, with possible Hebrew liturgical influences. The ashrei formula from the Psalms provides the clear background for makarioi, while concepts like anawim (humble poor), tzedakah (righteousness/justice), and shalom (peace/wholeness) deeply inform the vocabulary choices.

Some scholars have attempted to reconstruct possible Aramaic originals, though this remains speculative. What is clear is that the Greek text preserves Semitic thought patterns and theological concepts that would have been familiar to Jesus' Jewish audience while also making them accessible to Greek-speaking Christians.

Translation Traditions and Reception History

The translation of key terms has significantly shaped Christian interpretation across traditions:

- Dikaiosynē: Protestant traditions have often emphasized "righteousness" as right standing before God, while Catholic and Orthodox traditions have maintained stronger emphasis on justice and good works.

- Makarioi: Early translations favored "blessed" (Latin beati), emphasizing divine favor. Modern translations increasingly use "happy" or "flourishing" to capture the holistic well-being the term suggests.

- Ptōchoi tō pneumati: Debates over whether this "spiritualizes" poverty or describes a particular type of poverty have shaped how different traditions approach social justice and spiritual formation.

These translation choices reflect not just linguistic preferences but theological commitments about the relationship between faith and works, individual piety and social justice, present experience and future hope.

Septuagint and Second Temple Parallels

The Septuagint provides crucial background for understanding how Greek terms were used to translate Hebrew concepts. The Qumran texts offer additional parallels, including "blessing" formulas that share structural similarities with the Beatitudes (see 4Q525, 4Q185). These texts help situate the Beatitudes within broader Second Temple Jewish traditions of wisdom and apocalyptic expectation.

The Dead Sea Scrolls particularly illuminate the background of terms like "poor in spirit" (anawim) and "pure in heart," showing how these concepts functioned in Jewish sectarian communities that emphasized both social justice and ritual purity.

Conclusion: The Beatitudes in Their Original Tongue

The Greek text of the Beatitudes opens deeper understanding of Jesus' words by revealing:

- Makarioi describes present flourishing, not future reward conditional on behavior

- The blessings encompass both present realities and future consummations—they describe where true happiness is found now while promising ultimate fulfillment

- Terms like praeis, dikaiosynē, and katharoi tē kardia carry richer semantic ranges than single English words can capture

- The shift from third to second person in the final blessing personalizes the entire series for Jesus' followers

Through the poetry of the Greek, we hear echoes of Hebrew prophecy, Greco-Roman moral discourse, and the uniquely disruptive voice of Jesus. These are not passive virtues but active postures—ways of engaging the world that both reflect and participate in God's reign.

The linguistic analysis reminds us that the Beatitudes are not commandments to fulfill but a vision of who we are and who we are becoming in the light of the kingdom. They describe not achievements to be earned but gifts to be received—and in receiving them, to embody them for the healing of the world.

Understanding the Greek doesn't diminish the mystery of these ancient words but deepens it, showing how translation is always interpretation and how every generation must wrestle anew with what it means to live as citizens of the kingdom that Jesus proclaimed.

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources

- The Greek New Testament (Nestle-Aland, 28th Edition). Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2012

- Liddell, H.G., and Scott, R. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford University Press

- Bauer, Walter. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (BDAG). 3rd ed., University of Chicago Press, 2000

Scholarly Commentaries on Matthew

- Luz, Ulrich. Matthew 1--7: A Commentary. Hermeneia Series. Fortress Press, 2007 (Excellent on literary and theological structure; notes the inclusio in the Beatitudes and discusses translation options)

- Davies, W.D. and Dale C. Allison Jr. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew (Vol. 1). ICC Series. T&T Clark, 2004 (Definitive three-volume academic commentary; deep philological and theological analysis)

- Keener, Craig S. The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Eerdmans, 2009 (Rich in Greco-Roman and Jewish contextual insights; accessible yet scholarly)

Focused Works on the Beatitudes

- Allison, Dale C. The Sermon on the Mount: Inspiring the Moral Imagination. Crossroad Publishing, 1999 (An excellent synthesis of historical-critical, ethical, and pastoral insights)

- Pennington, Jonathan T. The Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing: A Theological Commentary. Baker Academic, 2017 (Modern evangelical approach; explores the translation of makarioi as "flourishing")

- Talbert, Charles H. Reading the Sermon on the Mount: Character Formation and Decision Making in Matthew 5--7. Chalice Press, 2004

Background and Language Tools

- Wright, N.T. The New Testament and the People of God. Fortress Press, 1992 (Helpful for understanding first-century Jewish and Greco-Roman worldviews)

- Kittel, Gerhard, ed. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (TDNT). Eerdmans, multiple volumes (Exhaustive word studies on Greek terms like makarios, dikaiosynē, praeis, etc.)

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. The Impact of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Paulist Press, 2009 (Provides helpful comparisons to Qumran texts using "blessing" forms)

Textual and Translation Studies

- Metzger, Bruce M. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. United Bible Societies, 1994

- Fee, Gordon D. New Testament Exegesis: A Handbook for Students and Pastors. 4th ed., Westminster John Knox, 2011

- Porter, Stanley E. How We Got the New Testament: Text, Transmission, Translation. Baker Academic, 2013