Echoes from the East: Confucian, Shinto, and Jain Wisdom in Light of the Beatitudes

"Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven."

—Matthew 5:3

A scholarly edition of this page, including full Chicago-style citations and a complete bibliography, is available in the Downloads section.

The Beatitudes often feel like a uniquely Christian vision. But when we expand our gaze eastward—toward Confucian, Shinto, and Jain traditions—we discover surprising harmonies. These traditions don't always use the same metaphysical language or share the same view of God. Yet each offers profound insight into living with integrity, humility, and compassion—the very qualities the Beatitudes elevate.

This is not an effort to equate all religions. But it is a way of tracing humanity's shared moral imagination across diverse landscapes, where virtue is rooted in discipline, relationship, and respect for all life. The Beatitudes may use different symbols, but their music echoes in these Eastern traditions, often with emphases on practice over belief and community flourishing over individual reward.

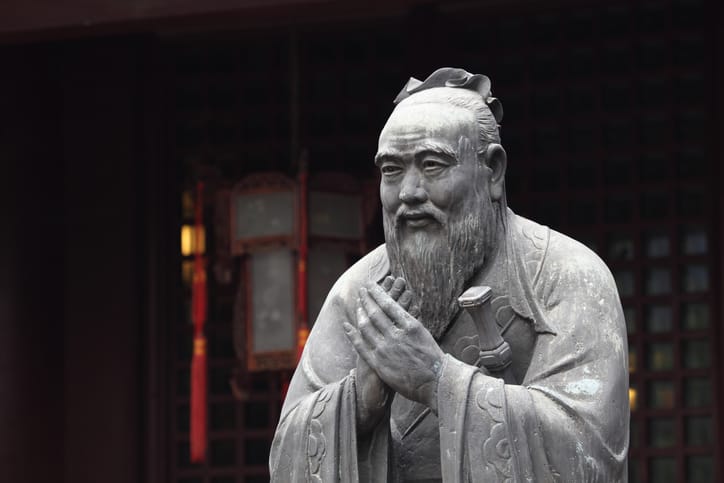

Confucianism: Harmony Through Virtue

Core Insight:

In Confucianism, the good life is about cultivating de (virtue) through ritual, respect, and relational responsibility. Ren (humaneness or benevolence), not wealth or power, is the true measure of a noble person.

While Confucius does not speak in terms of "blessing" or divine grace, there is a Beatitude-like ethos in his vision of the junzi—the "noble person" who exemplifies humility, moral restraint, and care for others. This mirrors the meek, the peacemakers, and those who hunger for righteousness.

One resonant passage comes from the Analects:

"The Master said: The noble person is not a vessel."

In other words, we are not tools for status or function—we are moral beings shaped by inner discipline and social harmony. The junzi practices shu (reciprocity)—not returning harm for harm but responding with understanding and restraint. This echoes the merciful who receive mercy.

The Confucian vision elevates forgiveness, patience, and compassion—virtues closely aligned with mercy and peacemaking. Confucian li (ritual propriety) creates communal spaces where these virtues are practiced collectively, much like how the Beatitudes envision transformed communities. But instead of divine inheritance, Confucianism emphasizes harmonious relationships and a flourishing society as the fruit of virtue.

How it resonates: Confucian ethics are grounded not in the promise of divine reward but in the restoration of moral order (li) and harmony (he) through right relationship. Both traditions understand that personal virtue serves communal flourishing, though they differ on whether the ultimate horizon is the kingdom of heaven or social harmony.

Shinto: Purity, Reverence, and Living in Alignment

Core Insight:

Shinto, the indigenous spirituality of Japan, is less focused on moral commandments than on kami—the divine forces in nature—and our harmonious relationship with them. Central to Shinto practice is the pursuit of makoto (sincerity), wa (harmony), and kegare (purity from defilement).

While Shinto lacks an explicit set of Beatitude-like teachings, it cultivates many of the same dispositions: reverence, humility, purity of heart, and respect for life. The ritual cleansing (misogi) recalls Jesus' emphasis on inner purity: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God."

Shrines aren't just sacred spaces—they are ethical landscapes, reminding us that the spiritual and natural realms are intertwined. Living rightly means living with gratitude, care, and sincerity—not for future reward, but because it honors the divine embedded in all things.

Regular participation in community festivals (matsuri) and purification rituals fosters a community-wide ethical orientation, similar to how the Beatitudes envision personal virtue contributing to collective transformation. The respect for kami also extends to environmental ethics and care for the land, echoing both purity of heart and "peacemaking" as living in right relationship with nature.

How it resonates: Shinto's ethical orientation is more aesthetic and relational than rule-based. There's little concern with sin or salvation, but a deep attentiveness to presence, place, and sacred balance. Both traditions value purity and harmony, though Shinto grounds these in cosmic rather than covenantal relationships.

Jainism: Radical Nonviolence and the Path of Restraint

Core Insight:

Jainism offers perhaps the most radical articulation of a Beatitude-like ethic in its commitment to ahimsa (nonviolence) toward all living beings. This extends to thought, word, and deed. Jains strive for complete harmlessness—not only to humans, but to insects, plants, and even microorganisms.

This deep reverence for life echoes "Blessed are the merciful," but even more closely aligns with "Blessed are the pure in heart" and "Blessed are the peacemakers." In Jain thought, peace is not a side effect of virtue—it is the virtue. The doctrine of anekantavada (the many-sidedness of truth) fosters intellectual humility and peaceful coexistence, paralleling the meekness that inherits the earth.

Monastics take this to the extreme, wearing masks to avoid inhaling bugs and sweeping the ground as they walk. But even lay Jains are called to gentleness, honesty, and spiritual discipline through vows and meditation. Jain compassion is not passive—it is enacted through daily disciplines and lifelong commitment to reducing harm.

Unlike Christianity, which emphasizes grace, Jainism is rigorously karmic: you reap precisely what you sow, and liberation (moksha) comes only through personal effort and purity.

How it resonates: Jainism does not rely on divine mercy or relationship with God. Instead, it teaches self-liberation through perfect nonviolence, self-restraint, and asceticism. Both traditions call for radical transformation of how we relate to others, though they differ on whether transformation comes through grace or disciplined effort.

Common Threads Across Eastern Wisdom

While each of these traditions is distinct, several shared themes resonate deeply with the Beatitudes, particularly in their emphasis on practice over doctrine and their vision of virtue serving communal harmony:

Practice Over Belief: A Shared Eastern Emphasis

These Eastern traditions share a distinctive feature: they prioritize right action and habitual disposition over doctrinal belief. In Confucianism, moral education through ritual practice shapes character. In Shinto, regular participation in purification and festival creates communal ethics. In Jainism, daily vows and disciplines gradually purify consciousness.

This practical orientation resonates with how the Beatitudes function as character-forming practices rather than abstract theological concepts. Both Eastern and Christian wisdom recognize that virtue must be embodied, practiced, and lived in community to become transformative.

Community and Individual in Balance

Another shared insight across these traditions is how individual virtue serves collective flourishing. Confucian self-cultivation aims at social harmony. Shinto personal purification contributes to communal and environmental well-being. Jain individual discipline reduces suffering for all beings.

This mirrors the Beatitudes' vision where personal transformation (poverty of spirit, purity of heart) naturally flows into social engagement (peacemaking, mercy, hunger for justice). The narrow path of virtue, whether framed as the junzi, the ritually pure, or the perfectly nonviolent, ultimately serves the healing of the world.

Modern Resonance and Contemporary Practice

These ancient wisdoms animate contemporary movements in ways that parallel the Beatitudes' ongoing relevance. Confucian emphasis on moral education and social harmony influences peace education and conflict resolution in East Asian societies. Shinto environmental ethics contribute to ecological preservation movements in Japan. Jain principles of nonviolence inspire contemporary animal rights activism and sustainable living practices.

Like the Beatitudes, these traditions offer not just historical wisdom but living practices that address modern crises of meaning, community, and environmental destruction.

A Theological Note

These Eastern paths are often less concerned with doctrine and more focused on practice. They do not always posit a personal God or heaven in the Christian sense. But they seek transformation—of self, society, and the world.

Where Christianity speaks of receiving the Kingdom through grace, these traditions teach alignment, purification, and harmony through disciplined living. Yet all point toward what Jesus calls "the narrow way": a path of humility, compassion, and moral courage that requires both personal commitment and communal support.

However, it's important not to forcibly equate Christian and Eastern goals, as their metaphysical frameworks and salvation visions remain quite distinct—even as their ethical outcomes overlap significantly.

How This Expands Our Understanding

Engaging Confucianism, Shinto, and Jainism expands the moral range of the Beatitudes—not by diluting them, but by enriching them. We begin to see how these virtues are not just Christian ideals, but human ones. Not limited to creeds or churches, but embedded in how people across cultures imagine the good, the true, and the just.

Jesus' teaching remains distinct—especially in its theology of grace and divine promise. But when read alongside these Eastern traditions, the Beatitudes are not less Christian; they become more universally compelling. They articulate a way of being that crosses boundaries while maintaining their particular power to transform both heart and community.

The Beatitudes, seen through Eastern eyes, reveal themselves as part of humanity's shared moral imagination—a vision of human flourishing that transcends religious boundaries while honoring the distinctive wisdom each tradition offers. In our interconnected world, these convergent insights suggest that the path of humility, compassion, and peaceful integrity remains as vital today as it was two millennia ago, whether walked in first-century Galilee, ancient China, imperial Japan, or medieval India.

References and Further Reading

Primary Texts

- The Analects of Confucius, trans. Arthur Waley (Vintage, 1989) -- Classic translation with helpful commentary

- The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki (Japanese foundational Shinto texts), trans. Donald L. Philippi and W.G. Aston respectively -- Ancient sources on Shinto mythology and practice

- The Tattvartha Sutra, trans. Nathmal Tatia (Jain Study Circle, 1994) -- Foundational Jain text on ethics and philosophy

- The Dao De Jing, trans. Stephen Mitchell (Harper & Row, 1988) -- For comparative context with Confucian thought

Commentary and Comparative Studies

- Huston Smith, The World's Religions (HarperOne, 2009) -- Accessible overview including detailed treatment of Eastern traditions

- William Theodore de Bary, Sources of Chinese Tradition (Columbia University Press, multiple volumes) -- Comprehensive collection of Confucian texts and commentary

- Yoshiro Tamura, Japanese Buddhism: A Cultural History (Kosei Publishing, 2000) -- Cultural context for understanding Shinto alongside Buddhist influences

- Padmanabh S. Jaini, The Jaina Path of Purification (University of California Press, 1998) -- Scholarly treatment of Jain ethics and practice

- Thomas Kasulis, Shinto: The Way Home (University of Hawaii Press, 2004) -- Modern scholarly introduction to Shinto thought and practice

- Julia Ching, Confucianism and Christianity: A Comparative Study (Kodansha, 1977) -- Direct comparison of ethical systems

Specialized Studies

- Tu Wei-ming, Centrality and Commonality: An Essay on Confucian Religiousness (SUNY Press, 1989) -- Contemporary Confucian thought and its spiritual dimensions

- John Whitney Hall, Japan: From Prehistory to Modern Times (University of Tokyo Press, 1990) -- Historical context for understanding Shinto development

- Paul Dundas, The Jains (Routledge, 2002) -- Comprehensive introduction to Jain history, philosophy, and practice

Comparative Religion and Ethics

- Mircea Eliade, Patterns in Comparative Religion (University of Nebraska Press, 1996) -- Classic work on religious symbolism across traditions

- Ninian Smart, The World's Religions (Cambridge University Press, 1998) -- Scholarly survey with attention to both similarities and differences

- Karen Armstrong, The Great Transformation (Knopf, 2006) – Study of the "Axial Age" that produced many of these wisdom traditions